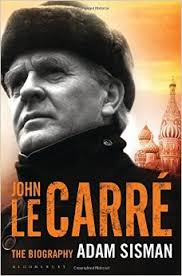

Adam Sisman. John Le Carre: The Biography

New York: Harper Collins, 2015.

As reviewed by Ted Odenwald

David Cornwell, more widely recognized by his pseudonym, John Le Carre, is a writer, the twists and turns of whose life are as complex as his plots. According to biographer, Adam Sisman, many of the actions, themes, and characters of Le Carre novels have their sources in Cornwell’s life. In fact, Sisman frequently demonstrates that Cornwell has mixed parts of himself into his characters: “…individuals inspired the characters that David created. But…’to turn real people into fictional characters, we have to supplement our limited understanding of them by injecting bits of ourselves….’” Having interviewed Cornwell several times, having access to the author’s archives including photos, and being able to communicate with Cornwell’s family, co-workers, publishing associates, and general acquaintances, Sisman has been able to shed light on one of Britain’s finest modern novelists.

David Cornwell, more widely recognized by his pseudonym, John Le Carre, is a writer, the twists and turns of whose life are as complex as his plots. According to biographer, Adam Sisman, many of the actions, themes, and characters of Le Carre novels have their sources in Cornwell’s life. In fact, Sisman frequently demonstrates that Cornwell has mixed parts of himself into his characters: “…individuals inspired the characters that David created. But…’to turn real people into fictional characters, we have to supplement our limited understanding of them by injecting bits of ourselves….’” Having interviewed Cornwell several times, having access to the author’s archives including photos, and being able to communicate with Cornwell’s family, co-workers, publishing associates, and general acquaintances, Sisman has been able to shed light on one of Britain’s finest modern novelists.

Cornwell’s youth was difficult: his mother, disgusted by her husband’s philandering and financial prodigality, abandoned the family when David was five. His father was a con-man whose whole life was built on scamming people, including friends and family, borrowing with no intention of returning, and setting up money-laundering schemes. With one parent absent and the other totally untrustworthy, David grew up lonely—except for his older brother, Tony. When their father was away, working one of his schemes, David and Tony were left with a physically abusive uncle. David’s education at Sherborne School was also isolating for him. Sisman suggests that there is evidence of Cornwell’s emotional scarring in many of the Le Carre novels: women are seldom presented as full characters; a major character’s troubled relationship with his father, especially in A Perfect Spy, suggests autobiographical self-examination, as do the troubled school years of several of his protagonists.

Sisman admits to having trouble with his research; Cornwell gives conflicting descriptions and explanations of various events in his life. The biographer explains where there are contradictions and attempts to resolve them, sometimes believing that Cornwell is caught up in his imagination, mixing fiction with fact. Actually, the resemblance of actions, characters, and attitudes in his novels to his own life is striking. His Oxford education led to his mastery of the German language and his fascination with German literature in spite of Great Britain’s animosity toward their long-term enemy. His linguistic skills led to his assignment to military intelligence—where he was stationed in Austria.

The questions most frequently directed at Cornwall relate to his having worked as a spy for MI5 and MI6. He does admit to having informed against students who had Communist sympathies, claiming that his loyalty to his country was greater than his loyalty to his friends. He found this spying to intensify his sense of loneliness: “There is something especially troubling about informing on those one knows personally; it feels like a betrayal of trust implicit in friendship. And befriending someone in order to betray him is perhaps even more so.” His detailed knowledge of the workings of spy networks certainly leads to speculation concerning the depth of his involvement with MI5 and MI6, though he claims to have held insignificant positions.

Much of this biography deals with Cornwell’s novels. Sisman focuses on the novelist’s work ethic; the novelist researches meticulously, visiting settings so that he can present details that convey the flavor of the world he is describing. In developing characters, he admits to drawing upon his acquaintances—sometimes creating composite characters. His working hours are long, and he works diligently in creating and revising. Sisman speaks of each novel’s production, including his negotiations with publishers and editors in Great Britain, Germany, and the U.S.

Sisman presents samples of positive and negative reviews of the Le Carre novels. A recurring question is the extent to which the novels had risen above the level of the spy fiction genre. Certainly the author’s popularity has been wide-spread, as indicated by the number of top-selling works, his enormous royalties, and the number of movies and T.V. series based upon his material. He occasionally has had bitter exchanges with other authors, most notably Salman Rushdie, whom Le Carre questioned about the wisdom of publishing The Satanic Verses. Occasionally, the subjects of Cornwell’s novels caused friction; The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, and The Looking Glass War depicted the intelligence service as being devious, disloyal to agents, incompetent, and self-delusional. He viewed “The Circus” as “…a microcosm of the British conditioning of our social attitudes and our vanities.” He often focuses grimly on the state itself, in its struggles “to come to terms with its post-imperial role.”

In his later years, Cornwell admits to being radicalized. He explores topics which clearly anger him. In The Night Manager he writes of the soullessness of an arms dealer; in another work, he explores racism directed against Muslims. In Single and Single he attacks corporate greed within a British merchant banking house, which has united with criminal elements. In The Constant Gardener, he attacks pharmaceutical exploitation in Africa. Companies were falsifying clinical trials; they were using humans in poor countries as guinea pigs; they “dumped inappropriate or out-of-date medicines—suppressed information about contra-indicators and their side-effects.” Absolute Friends, which Sisman calls “a novel of fist-shaking rage,” attacks America’s abuse of power. He attacks colonial exploitation, political hypocrisy, and assaults on civil liberties in The Mission Song. He writes a “state of the nation novel” in Our Kind of Traitor, exposing the “corruption of British society by greed.” He demonstrates the “pernicious effect…penetrated deep into the institution of government, the civil service, and …the intelligence services.”

Through his decades of writing, Cornwell has been an enigmatic figure, not particularly comfortable with public exposure—and generally reluctant to discuss his family and his background in intelligence. Sisman’s study is exhaustive, and while the biographer admits that there are many unclear elements in his subject’s background, the overall picture of the novelist comes through clearly.

Ted Odenwald and his wife, Shirley have lived in Oakland for 44 years. He taught HS English at Glen Rock High School for all of those years plus one more. Now he is enjoying time spent with his family, singing in the North Jersey Chorus and quenching his wanderlust. Ted is also the Worship Leader at the Ramapo Valley Baptist Church in Oakland.

Ted Odenwald and his wife, Shirley have lived in Oakland for 44 years. He taught HS English at Glen Rock High School for all of those years plus one more. Now he is enjoying time spent with his family, singing in the North Jersey Chorus and quenching his wanderlust. Ted is also the Worship Leader at the Ramapo Valley Baptist Church in Oakland.