Boroughitis

The NJ Disease That Created Oakland

By Kevin Heffernan

On April 8, 1902 Oakland seceded from Franklin Township by an act of the New Jersey Legislature. Hurrah! And in the words of Martin King, Jr., we finally were “Free at last, free at last, thank God almighty we are free at last!”

While I will soon write far more about the details of this wondrous event, it’s important to do some stage setting with regard to the state and county geo-political environments in 1902. In other words, what was going on around us to enable the huge step of secession that has benefited both you and me mightily since. How did the forefathers of this town pull it off and what was going on in Bergen County at that time?

In a word New Jersey had gone nuts in 1894 and the folks in Bergen County very eagerly and very quickly followed. Huh?

The ‘Disease’

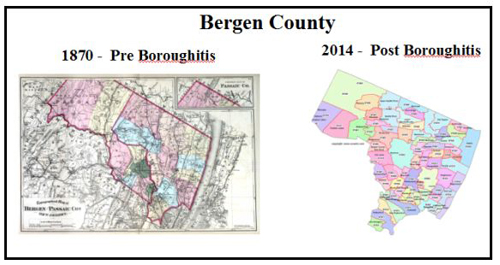

Consider for a moment that Bergen County has no fewer than 70 individual and very distinct towns with 70 mayors, police and fire departments, school systems, road departments, and forever so forth. And how did New Jersey, the third smallest state in the USA come to have no fewer than 565 individual incorporated towns, villages and municipalities? Heck, Texas has ZIP codes larger than Bergen County.

In yet another word, it was called Boroughitis. Some might describe Boroughitis as a late 19th Century general disease in New Jersey characterized by accumulating tax ratables with the symptom of severely short-sighted egos. Huh? This is not at all to suggest that the secession of Oakland from Franklin Township fits this mold. It didn’t as our gripes (reasons) were both real and documented. as we will see in the near future. But the disease did provide the opportunity to be masters of our own fate….for better or for worse.

OK, back to Boroughitis.

In 1894 most of New Jersey was governed by townships as political and administrative subdivisions of counties. In that year the New Jersey State Legislature in its infinite wisdom passed a law that permitted any contiguous number of homeowners to secede from the township and form its own municipality. During earlier times when new townships were formed, they assumed a portion of the debt of township from which they seceded. That seemed fair since townships were responsible for building and maintaining roads and schools as well. However, there was one provision of the 1894 law that got the immediate attention and full embrace of every politician in New Jersey who had a pulse and maybe even a few that didn’t.

Specifically, that wonderful law of 1894 did not require seceding municipalities to assume any portion of the accumulated debt of the township from which it seceded. And the formation of municipalities were not limited to the geographical boundaries of the township they were seceding from. (Time for another Huh?) That means that the group of contiguous residents could leave a township without the tax burdens of either roads or schools. A state senator at that time decried that the law was insanity.

To be sure, there were clear political motivations propelling Boroughitis. More towns=More Mayors and Councils=More Republicans or Democrats in Power=More Seats on the Board of Elected Freeholders and so forth. It was not at all the simple, idealistic notion of democracy wherein people ought to be free to determine their destiny. Some things just never change.

The Roots

Starting in 1894 new municipalities would start with a clean slate and govern and tax themselves to provide these township-sponsored services themselves. Wow! But, that also meant that they would be required to tax their own residents for these and all other services. And who wants to pay taxes? But alas, there was a solution and it was called ‘ratables’. A ratable is anything that is taxable….homes, land, improvements, commercial buildings, factories and anything that is not owned by the municipality. If it looks taxable, it usually is taxed and these ratables feed the municipal coffers that provided all the services that a town provides.

Since homeowners of any time or era don’t particularly like to pay taxes, the solution became immediately obvious to the creators of new municipalities: Make sure that one’s new municipal boundaries included as many industrial and commercial buildings as possible and make sure that they were as large as possible such that they would pay most or all of the taxes in town. There were so many pennies from heaven that in 1894 alone, no fewer than 23 new towns were formed in Bergen County. Map makers could not keep up. Local politicians believed that they could do it better, faster and cheaper than the township in addition to being the master of their own fate. That attitude might be considered a bit of innocent hubris.

This obvious approach also led literally to a feeding frenzy among local politicians to draw, redraw and redraw again their municipal boundaries to include as many factories and commercial buildings and all other non-residential things taxable as possible. Municipalities were formed one day only to figure out that they should re-form because there was a major ratable down the road.

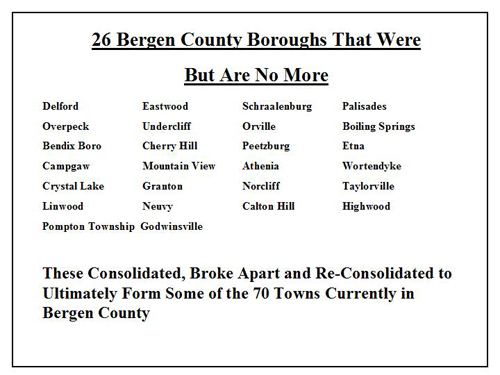

Towns Come and Towns Go

So, many municipalities would come to be (incorporated), then cease their existence and redraw their municipal map into a new town. If you think that this sounds silly, just consider that there no fewer than 26 towns in Bergen County that were created between 1894 and 1900 but no longer exist. Who can forget the towns of Neuvy, Athenia, Granton, Norcliff, Etna or even Taylorville to name just a few? Oh, did I fail to mention Peetzburg, Delford or Orville? The list of never-to-be towns in Bergen County goes on.

The short answer is that everybody abandoned their recently favorite town name and municipal map for the sake of greater ratables to feed the municipal coffers and lower residential taxes. Remember that each new municipality was now responsible for its own roads and schools in addition to the myriad other services for its citizens. And, no, downtown beautification, tennis courts and rec fields were not even in their vocabulary at the time. Their mind set was limited to the basic things that make a town work and be called a town.

Effect Upon Oakland

I’m quite certain that this municipal chaos drove local post masters nuts. And I’m equally certain that, after 8 years of this environment in Bergen County, it had its effect upon Oakland’s founders. They saw no deference to geographic or historical loyalty. They witnessed changing local selfish best interest flourish and become the norm of the day. Perhaps and most importantly, they realized that if others can secede regardless of true necessity, then why not they. Even though Oaklanders were considered as pumpkin dusters by those on the eastern side of the county generally and by Franklin Township officials in Ridgewood specifically, they felt the righteous indignation of being screwed by the folks in Ridgewood as it was the administrative capital of Franklin Township.

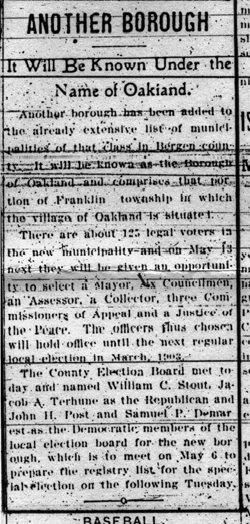

By 1902 the insanity of Boroughitis had been running amok for a full 8 years. Towns came and towns went and town boundaries were written in pencil only to be erased and changed with the next wave of political and ratable sentiment. And even the newspapers of Bergen County were suffering from Boroughitis fatigue as evidenced by the ‘breaking news’, stop-the-presses reporting of the independence of our Oakland. The headline of the small space announcement on page 6 of The Record on April 9, 1902 whimpered “Another Borough” in a 149-word article as if in journalistic exhaustion. To add insult to injury, even the name of our beloved village was misspelled as ‘Oakinad’ in the sub-headline.

By 1902 the insanity of Boroughitis had been running amok for a full 8 years. Towns came and towns went and town boundaries were written in pencil only to be erased and changed with the next wave of political and ratable sentiment. And even the newspapers of Bergen County were suffering from Boroughitis fatigue as evidenced by the ‘breaking news’, stop-the-presses reporting of the independence of our Oakland. The headline of the small space announcement on page 6 of The Record on April 9, 1902 whimpered “Another Borough” in a 149-word article as if in journalistic exhaustion. To add insult to injury, even the name of our beloved village was misspelled as ‘Oakinad’ in the sub-headline.

When Oakland first became an incorporated borough, Ed Page, our then future second mayor, was then charged with making a tax assessment valuation of every taxable structure (ratable) in Oakland inclusive of his mansion and farm, the Calderwood, Wilkins Brush factory and the gun powder works. The calculated grand total for the entire borough of Oakland was slightly more than $420,000! And on that taxable amount, we founded a town, paved our roads and built our first school, PS #1 still standing on RVR. Damn, those Dutch founders of Oakland were good!

Post Script

As a footnote, I have to add that Oakland today is part of the 70 towns in Bergen County that came to be since 1894. And the initial promise of lower cost government has in fact proved to be a false god. Precisely the opposite is true. Nonetheless, Oaklanders are very justifiably proud of our small town, the village that we love. That said, were it not for the insanity of the enabling Boroughitis legislation starting in 1894 and the likes of David C. Bush, Sr., we might not be the town of Oakland today with our unique identity and heritage.

For me, I’ll suffer each of the arrows of the cost of independence to keep and enhance the pride and history of who we uniquely are as a community. While logic and common sense suggest that there ought to be municipal reconsolidation for the sake of both municipal efficiency and budgets (lower taxes), we can fix our deficiencies and inefficiencies that reside in the margins of our municipal budget while keeping the core of who we proudly are. True, our property values might be greater if we were part of either Franklin Lakes or Wyckoff. But our heritage and community pride would be forever lost. No thanks, I’ll keep Oakland. It’s kinda great here.

kheffernan555@gmail.com