The Strategy Behind Great Oak Park

By Mike Guadagnino

Parks And Recreation

While Great Oak Park is in its development phase, it would be interesting to pause for a moment and examine the behind the scenes strategy in advancing the mission. From the onset, the park’s progress has used the past to minimize mistakes and duplicate successes. Oakland has been genuinely studying the history of famous American parks from their birth to present day glory.

While Great Oak Park is in its development phase, it would be interesting to pause for a moment and examine the behind the scenes strategy in advancing the mission. From the onset, the park’s progress has used the past to minimize mistakes and duplicate successes. Oakland has been genuinely studying the history of famous American parks from their birth to present day glory.

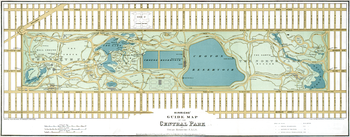

Past models are being studied and three major American parks are the focal point. Central Park, Boston Common and the Chicago Park system are grand projects that suffered with problems but ultimately enjoyed triumph.

In the early years of New York City, there was a practical debate over the need as well as desire for New Yorkers to have their own grand park. Over much discussion and negotiating the central park area was identified and marked as the place for such grounds. In the spirit of inclusiveness a contest was held for a winner to create a topography and character for the new park. The winner was a man by the name of Fredrick Law Olmstead who designed the project with his business partner Cavlert Vauz. Olmstead was then selected to oversee the building of this magnificent project. As the development proceeded Olmstead butted heads with the city and was eventually removed from his appointed position.

Development took a prolonged 30 years for the park to be completed. Some of the issues that dragged the project included the eviction of poor people living on the property, the ambitious scale of construction and political back biting. What started as a democratic idea became a large scale boondoggle. Once the park was completed it slowly developed the character and aesthetics of a majestic park. The fate of the park reversed in the first half of the 1900’s as it went through a period of deep neglect. The reason for the inattention was blamed on the lack of any political gain politicians may receive by caring for the park. Legislators of the day only did things that helped them garner votes, and park stewardship was not one of them. The back half of the century saw a more idealistic approach as many wanted to see the park used for events, sports and theater. The park saw a rebirth in the later years and was restored to the glory of its youth.

The Boston Common is the oldest city park in our country. It has an eclectic history which includes the encampment of British troops, a revolutionary burial ground and was the place of the hangings; some of the more famous hanged were Mary Dyer and Ann Hibbins. The park was once used as a cow pasture, a place for pre-revolutionary riots and Vietnam War protests. Although many parks can claim some of what the Common has experienced, none can claim all of it.

The park began major improvements in the 1700’s, well before most parks were even an idea. In the 1830’s the Common had installed its signature ornamental iron fencing. The park, like many other parks, slowly grew within its borders to identify with the times while remaining a city oasis. The park has been a location that many famous political and religious leaders used as a place to give dramatic speeches. Although the Boston Common is a modern park with a band shell, memorials and a walking path, it still holds that special New England charm.

The Chicago park system is different in many ways, which makes it a perfect complement to the two east coast parks. When the city first became incorporated there was a large push from many residents to preserve the land next to the lake as open space. As the city developed, real estate investors realized the positive potential small open space lots had on overall property values. Chicago was in the forefront of the importance in green space. Although NYC does have numerous small parks located within its borders (i.e.; Bryant Park, Columbus Park, and the Bronx Zoo etc.), Chicago actively designed open green space as a way of making their city more valuable and more beautiful. In fact Chicago looked to the past and used cities like New York and Paris to learn how to actively develop a system of parkland.

So what can Oakland learn in 2014 and use for Great Oak Park? In the same way Central Park began its early development process in a very democratic way, so has Oakland. Open meetings, open discussions and a full blown “name the park” election were all part of the process. Oakland can also learn how Boston handles its negative park history as today and tomorrow’s residents will have to tell the story of the Jamaican Day Jamboree. Like Chicago, almost two centuries ago, Oakland can learn valuable lessons by looking to and learning from past developments.

Some past city park advances suffered from political back-biting, enlarged egos and jealousy, which only hindered and destroyed the creative process. In contrast when everyone moves together, which includes allowing the past to participate, discussing the ideas of the present and having an eye on the future, creativity follows a positive definitive direction. Great Oak Park has been very inclusive of the past while protecting the legacy of the native-Americans and celebrating its more recent past, the Pleasureland and Muller’s Park era. Those in today’s Oakland discuss the protection of the river and stream, looking to fund raise for a budget and volunteer our efforts so we may enjoy the park. Young residents have been included as to what they would like to see in their park; they will be the future care takers and it is important to give them to the tools so Great Oak Park does not suffer with a period of neglect similar to the Central Park mistake of the 20th century. Oakland also sees, like Chicago saw the value of turning a small area of nothing into a park for increased home and property values.

This is a project where everyone has an eye on hometown pride and today’s Oakland can be the generation that builds a park uniquely ours. So let’s continue to learn from the past, and create a future that generations may one day use as a tool to study how park development can be done correctly.