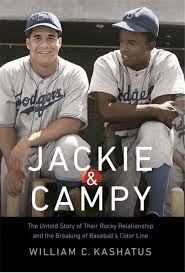

William C. Kashatus. Jackie and Campy: The Untold Story of Their Rocky Relationship and the Breaking of Baseball’s Color Line. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2014.

As reviewed by Ted Odenwald

The names “Jackie” and “Campy” conjure up for me countless exciting memories of two great ballplayers on my favorite team, the Brooklyn Dodgers. To a pre-teen baseball fan, these men were what I thought baseball was all about: power, skill, determination, and winning. I was unaware of the racial discrimination that clouded both of their careers; nor did I know that they were among the forerunners of a civil rights movement.

The names “Jackie” and “Campy” conjure up for me countless exciting memories of two great ballplayers on my favorite team, the Brooklyn Dodgers. To a pre-teen baseball fan, these men were what I thought baseball was all about: power, skill, determination, and winning. I was unaware of the racial discrimination that clouded both of their careers; nor did I know that they were among the forerunners of a civil rights movement.

The recent movie, “42,” dramatized the harrowing early years of Jackie Robinson’s crossing baseball’s color line, a line drawn in a gentleman’s agreement among baseball team owners. Kashatus adds to the details of bigotry portrayed in “42”: the ferocity of the verbal and physical abuse leaving a blot on the history of Major League Baseball. Robinson’s restraint in the face of blatant prejudice now seems incredible given the athlete’s fiery temperament. Yet his fulfilling a covenant with Dodger owner, Branch Rickey, to refrain from retaliation opened the door for many African American baseball greats, including Roy Campanella, an outstanding catcher in the Negro Leagues. The author reveals that there were strong undercurrents of tension among players of the same race: some demanding treatment equal to that of whites; others believing that passive acceptance of their lot would lead to their acceptance by the white establishment.

Kashatus stresses that Robinson and Campanella were far apart in their attitudes towards race relationships. This book “…offers an important corrective to what has become a sentimental retelling of their relationship and its impact on baseball’s integration process.” What had begun as a mutually supportive interaction in the late ‘40’s, became a contentious rivalry by the mid ‘50’s, sparked perhaps by jealousy, but certainly by philosophical differences. The author believes that the two athletes’ bitterness resulted from “…a conflict instigated by a fundamental dialectic in African American History—one that embodies a constant but inevitable tension between active defiance and passive resistance, aggression and docility, direct action and self-reliance.” Campanella’s behavior was aligned with the thinking of Booker T. Washington, who believed that “…African Americans would progress only by winning support from the better sort of whites and by working hard, living …moral lives, and supporting black enterprises.” Washington worked to convince white society that blacks would accept social segregation and disenfranchisement in exchange for educational and economic opportunities.” Believing that racism attacked his manhood, Robinson appeared to align himself with the activist W.E.B. DuBois, “…who promoted integration of the races and full citizenship for blacks. He demanded an end to racial discrimination in education, public accommodations, voting and employment.”

Jackie and Campy got along well in their early years as teammates, probably because Jackie was refraining from retaliation against bigotry, while Campy was content to let his playing do his talking. Some African American athletes believed that Campanella might have been the better choice for breaking the color barrier, but Branch Rickey had several reasons for choosing as he did: Robinson was educated (at UCLA); he was a well-rounded athlete; he was articulate; Campanella had dropped out of high school; though a gifted catcher and hitter, he would have been under tremendous pressure trying to control the efforts of a pitching staff, some of whom were bigoted. After Robinson’s covenant with Rickey expired, he became increasingly aggressive, retaliating when harassed or physically “assaulted.” He challenged umpires, berated teammates, especially those who had initially signed a petition refusing to play ball with blacks—and later, any African American who did not share his activist views. Campanella feared that being an activist could cost him his job, baseball being the only work for which he was prepared. Self-reliance, dedication to his work, and grateful acceptance of whatever was handed down to him gained him the admiration of writers, players, and fans. But eventually, his behavior drew the disdain of Robinson, who labeled Campy “an Uncle Tom.”

Jackie’s anger intensified when his two strongest advocates, baseball commissioner Happy Chandler and Branch Rickey, left the scene. Chandler had allowed Rickey to bring Robinson into the major leagues in spite of the objections of other owners; Rickey had been driven out of the Dodger organization by Walter O’Malley, who clearly favored Campanella’s acceptance of the company line to Robinson’s aggressive advocacy for civil rights. Kashatus suggests that Jackie may have been jealous of Campy, whose laid-back behavior and sense of humor won him much popularity; he had also won three MVP awards—to Jackie’s one. Campy, on the other hand, was annoyed that that Robinson had gained all of the credit for breaking the color barrier. Campy said that the credit should have been spread around: “without the [Dodgers}…, you don’t have Brown v. Board of Education. We were the first ones down south not to go around the back of restaurants, the first ones in the hotels. We were the teachers of the whole integration thing.” Their differences grew into a feud when a hotel refused to register black players. Robinson insisted on confronting management and staying in the hotel. Campy refused to become involved. While the incident may not seem to have been all that significant, it highlighted Jackie’s fiery antagonism as he berated Campy publicly, deepening the catcher’s resolve to stay out of the spotlight.

They finally reunited and reconciled about 10 years after retiring, each having had his life tragically altered. Campanella had suffered a severe spinal cord injury in 1958, leaving him paralyzed below his shoulders. Robinson struggled with the ravages of diabetes, losing sight in one eye.

Kashatus’ analysis of this progressively strained relationship may disappoint the fans for whom Ebbets Field was the shrine of great teamwork, competition, and athleticism. Yet the author is convincing in his view that Robinson and Campanella personify the quest to discover the most productive avenue for acceptance and equality for all African Americans. “Baseball became the great equalizer, the one institution that allowed everyone to start on equal footing, regardless of race or ethnicity.” But the path was not always smooth, leading to the estrangement of great athletes who had the most to gain by working together.

Ted Odenwald and his wife, Shirley have lived in Oakland for 43 years. He taught HS English at Glen Rock High School for all of those years plus one more. Now he is enjoying time spent with his family, singing in the North Jersey Chorus and quenching his wanderlust. Ted is also the Worship Leader at the Ramapo Valley Baptist Church in Oakland.

Ted Odenwald and his wife, Shirley have lived in Oakland for 43 years. He taught HS English at Glen Rock High School for all of those years plus one more. Now he is enjoying time spent with his family, singing in the North Jersey Chorus and quenching his wanderlust. Ted is also the Worship Leader at the Ramapo Valley Baptist Church in Oakland.