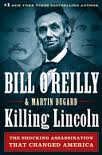

Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard. Killing Lincoln: The Shocking Assassination That Changed America Forever

Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard. Killing Lincoln: The Shocking Assassination That Changed America Forever

New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2011.

As reviewed by Ted Odenwald

Click here listen to Bill O’Reilly narrating the audio book version.

Despite repeated warnings that his life was in danger, President Abraham Lincoln continually moved about with minimal security. Was this behavior the result of foolhardiness, bravado, courage, war-weariness, or indifference bred by his awareness of his unpopularity? Despite the fact that Lee’s surrender had terminated the Confederacy’s secession and attempts at self-determination, John Wilkes Booth proceeded with his plans to support “the cause.” Was he a vengeful Southern sympathizer, a blowhard seeking notoriety, a dreamer, who believed that only he could alter the outcome of the war, or was he an insanely obsessive hater of the man who stood against white supremacy and slavery?

These issues resurface repeatedly in this fascinating interpretive historical study by O’Reilly and Dugard. And while these questions may never be fully answered, the reader cannot help but wonder: how could Lincoln be so seemingly indifferent about his safety; why would Booth willfully throw away his successful acting career?

According to the authors, Lincoln fully expected to be killed while in office, for he was the most reviled President in U.S. history. But he resolved to carry on: “Rather than dwell on death, Lincoln prefers to live life on his own terms. ‘If I am killed I can die but once…but to live in constant dread is to die over and over again.’” Interestingly, a favorite source of solace for the President was Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar—in fact his attitude towards death echoes Caesar’s famous lines, “Cowards die many times before their deaths;/ The valiant never taste of death but once.” Early chapters of this book deal with the closing days of the war as Lincoln moved from the safety of City Point to the battlefield at Petersburg and then on to Richmond with very little protection—a prime target of opportunity for a sniper or a vengeful citizen. In Washington, he would walk in a crowd unprotected—or would speak to a crowd who had not been properly screened. The White House was open to anyone who sought the President’s favor. To escape the political turmoil of the capital, Lincoln would ride in a lightly guarded carriage on an unprotected, remote road. On the very night of his assassination, having received warnings about rumored threats, he went to the theater with little protection and thus became an easy victim.

Hoping to dramatically revitalize the Confederacy, Booth had originally become involved in one of several plots to kidnap Lincoln, playing over and over again in his mind how he would humiliate the President both physically and mentally. But with Lee’s surrender, Booth turned his goal to murder: revenge for bringing ruinous war upon the South; revenge for breaking the institution of slavery; and revenge for the hundreds of thousands killed and wounded. Booth believed that he would be the avenging angel, gaining more notoriety and gratitude than any stage performance could. He was so committed to the act, so committed to gaining fame, that he sent a letter to a local paper shortly before the act, taking credit for the killings of Lincoln, the Vice-President, and the Secretary of State. Once the letter was sent, there could be no backing down.

If Booth’s plan was madness, there was definitely method to it. O’Reilly and Dugard traced the assassin’s careful plotting: recruiting his team of co-conspirators; withholding key elements of the plot, including the intent to murder, until the last possible moment; physically mapping out and rehearsing his escape route; determining the exact time at which all three killings would take place; and scouting the Ford Theater for a secure approach to the President’s box, and a quick, safe means of evading pursuers.

In addition to all the careful planning, Booth had a great deal of good luck. He knew that Lincoln would be attending a performance at Ford’s Theater and even knew exactly where the President would be seated; Booth had overheard the theater’s owner directing a stagehand to decorate the President’s booth. The actor knew the play to be performed, Our American Cousin, inside and out, and knew precisely when there would be a loud audience reaction that would mask a small arms report. Booth was able to gain easy access to Lincoln’s booth because the bodyguard had abandoned his post and was in the tavern next door to the theater; Additionally, Booth was able to escape from Washington when telegrams alerting the Army to search for the assassin were not sent. Also, bridges connecting Washington with either Maryland or Virginia should have been closed for a curfew, but were in fact left open.

The authors detail Lincoln’s last hours, beginning with the heroic efforts of a young military doctor, Charles Leale, to relieve pressure in the President’s badly damaged brain, his administering CPR, and also his applying mustard plasters to stimulate the dying man’s nerves. As everyone realized that the wound was mortal, the Surgeon General and the future Surgeon General both attended Lincoln while more than five dozen “people of influence” paid their respects.

The pursuit and apprehension of the conspirators comprise several of the closing chapters. Booth was fatally wounded in a barn in Virginia. Lewis Powell, who viciously stabbed Secretary of State Seward, was apprehended after he lost his way and returned to Mary Surratt’s home as she was being arrested as an accomplice. George Atzerodt, who was too frightened to attempt the assassination of Vice-President Andrew Johnson, would have escaped cleanly had he not spoken approvingly of the assassination while he drank at a tavern.

O’Reilly and Dugard present a number of interesting issues, some of which have led to broader conspiracy theories. There are many questions concerning the possible involvement of Secretary of War, Edward Stanton. Why, they ask, did Booth decide to spare the life of the Secretary of War, when it was the actor’s objective to topple the government? Why did Stanton refuse to allow MAJ Thomas Eckert to serve as Lincoln’s bodyguard on the fateful night—especially since Lincoln knew and trusted the Major, and actually requested that he be assigned? Why did Stanton not push for punishment for John Parker, the delinquent bodyguard who abandoned his post to go for a drink? Why did Stanton hire Lafayette Baker, a detective whom the Secretary had previously dismissed in disgrace, to track down Booth? Why did Stanton confiscate and lock up Booth’s diary, refusing to reveal its contents? Why, when he finally released the diary, were 18 pages missing? Why did a sergeant, though ordered not to harm Booth, fatally wound him? And why was that soldier later rewarded for his action?

Killing Lincoln is certainly not dry history. It captures the drama of a period that was filled with wildly emotional contrasts: the jubilation of the North and the violent frustration of the South; the hope for peace and reconciliation filling every thought of the President and the maniacal hatred for Lincoln, as typified by Booth; the sinister maneuverings of the conspirators and the innocent vulnerability of the Chief Executive, who expected to be killed; the murderer’s desperate race for refuge, and the vengeful actions of the government’s officials and courts.

Ted Odenwald and his wife, Shirley have lived in Oakland for 42 years. He taught HS English at Glen Rock High School for all of those years plus one more. Now he is enjoying time spent with his family, singing in the North Jersey Chorus and quenching his wanderlust. Ted is also the Worship Leader at the Ramapo Valley Baptist Church in Oakland.

Ted Odenwald and his wife, Shirley have lived in Oakland for 42 years. He taught HS English at Glen Rock High School for all of those years plus one more. Now he is enjoying time spent with his family, singing in the North Jersey Chorus and quenching his wanderlust. Ted is also the Worship Leader at the Ramapo Valley Baptist Church in Oakland.