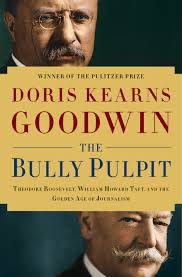

The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism

by Doris Kearns Goodwin

New York: Simon and Schuster, 2013

As Reviewed by Ted Odenwald

Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft became good friends as they worked together to achieve the goals of the progressive movement in the Republican Party in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These goals included balancing the distribution of wealth, regulating the great corporations and railroads, strengthening the rights of labor, and protecting natural resources. Their visions and combined efforts, supported by the in-depth investigative reporting of the prominent journalists of McClure’s Magazine, led to major changes in the directions of America’s social, economic, and political institutions. Roosevelt and Taft became particularly close during Roosevelt’s 7-year presidency, even though their personalities and temperaments were diametrically opposed. These differences eventually led to a bitter split, in which Taft, Roosevelt’s successor and protégé, was undercut and assailed by his mentor—and the Republican Party, now split into two camps, lost its grip on the government.

Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft became good friends as they worked together to achieve the goals of the progressive movement in the Republican Party in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These goals included balancing the distribution of wealth, regulating the great corporations and railroads, strengthening the rights of labor, and protecting natural resources. Their visions and combined efforts, supported by the in-depth investigative reporting of the prominent journalists of McClure’s Magazine, led to major changes in the directions of America’s social, economic, and political institutions. Roosevelt and Taft became particularly close during Roosevelt’s 7-year presidency, even though their personalities and temperaments were diametrically opposed. These differences eventually led to a bitter split, in which Taft, Roosevelt’s successor and protégé, was undercut and assailed by his mentor—and the Republican Party, now split into two camps, lost its grip on the government.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, in her inimitable style, details the political careers of these two powerful figures. “Though the two men had strikingly different temperaments—Roosevelt’s original and active nature at odds with Taft’s ruminative and judicial disposition—their opposing qualities actually proved complementary, allowing them to forge a camaraderie and rare collaboration.” Modest and straightforward, Taft was known to be easy-going, warm, and sociable, “finding common ground with all.” He always worked within a defined framework, eventually developing a “judicial habit of thought and action.” Roosevelt was less approachable, unless he saw ways in which interaction could serve his purposes. He seemed to be in perpetual motion, seeing all activities as “intellectual adventures.” Not satisfied with; the sedentary requirements for judicious evaluations, his study of the law served to “facilitate his diverse values” in his long list of public offices.

Though Roosevelt sought the spotlight while Taft shunned it, each man worked for similar causes that eventually drew them together. As a prosecutor in Cincinnati and then as a state superior court justice, Taft fought corruption in government as well as misconduct by large corporations. Roosevelt, as a New York state legislator, sought to expose and condemn corrupt politicians and judges. Their efforts earned them notable positions: Taft was appointed U.S. Solicitor General by President Benjamin Harrison, and Roosevelt was appointed New York City police commissioner and then to a Civil Service Commission post. They became close friends in Washington, working hard to eliminate the spoils system. Just as their clout increased, so did their targets, as they eventually took on giant conglomerates such as Standard Oil, Addyston Steel, and Northern Securities. “…their experiences as police commissioner and circuit judge had awakened both to the harsh circumstances confronting their nation’s working poor and sensitized them to question the laissez-faire doctrine that had guided them since their days in college.”

As Taft and Roosevelt were honing their political skills, they acquired powerful allies in the investigative press. Sam McClure had assembled a team of outstanding journalists—Ida Tarbell, William Allen White, Lincoln Steffens, and Ran Stannard Baker—who published several series of studies of individual and corporate abuses of power and wealth. Their work aroused public indignation and provided fuel for governmental investigation and intervention, “thus vindicating and supporting the efforts of Taft and Roosevelt.” One masterwork by Tarbell was a series about Standard Oil, detailing Rockefeller’s alliance with railroads. Growing to hate any kind of privilege, Tarbell examined the “wrongs” which led to the unequal distribution of wealth: “discriminatory transportation rates, tariffs [used] for revenue only, private ownership of natural resources.” Baker, a labor reporter based in Chicago, covered the Pullman strike and wrote many articles about the poor working class. Steffens, having developed radical social ideas in Europe, carried his values into his coverage of the New York City police. He also conducted studies of municipal and state corruption. White examined the injustices in the farming and freight industries.

With journalists stirring up popular support for the progressive movement, Roosevelt and Taft, bound closely in friendship and philosophy, rose respectively in the government. Roosevelt became Secretary of the Navy, Governor of New York, Vice President, and eventually, following McKinley’s assassination, President. Taft served as circuit court judge, but then took great pleasure, and was highly respected, as a judicious peace-keeper in his position of Governor General of the Philippines. He left that position with regret when President Roosevelt insisted that he return to D.C. to become Secretary of War—an appointment that he didn’t particularly want because he knew that the cabinet position was going to be politically pressure-filled.

With the unofficial assistance of McClure’s writers, Roosevelt was able to take strong progressive initiatives including an anti-trust suit against Northern Securities Company, which “controlled tens of thousand of miles of tracking spanning the continent and hundreds of ships.” This company acted as “an absolute dictator in its own territory, with monarchical powers in all matters relating to transportation.” Roosevelt also brought action against the Beef Trust and warned J.P. Morgan and U.S. Steel.” He also moved to set aside large portions of America’s land for preservation purposes—especially to avoid their exploitation by conglomerates.

Taft and Roosevelt were in accord for years, though their methods of operation were quite different. When Roosevelt chose not to run for a third term, he strongly supported Taft to be his successor. Unfortunately for Taft and the Republican Party, Roosevelt believed that there was only one way to do things—his way. Taking credit for most of Taft’s political accomplishments, Roosevelt expected Taft to continue in his footsteps as a fiery, radical progressive. But Taft, ever judiciously minded, moved more cautiously than his mentor. He compromised on many issues that Roosevelt would have fought ferociously. Taft committed the “ultimate sin” by firing Roosevelt’s director of forestry and natural preservation and by agreeing to compromises in issues affecting labor and the equal distribution of wealth. Progressives charged the sitting president with betrayal of his party.

Most painful to Taft was the series of vituperative attacks launched at him by his “friend,” who attempted to replace him as the Republican presidential candidate in 1912. Whenever taking issue with a person’s thoughts, Roosevelt would attack the person as well as his ideas. Roosevelt called Taft weak, indecisive, and dishonest. Taft, in response, claimed that Roosevelt was dangerous to the people. Roosevelt retorted that “{Taft} only discovered I was dangerous to the people when I discovered he was useless to the people.” The anger that had been dividing the party for years finally turned into an outright rebellion when conservatives and progressives battled on the seating of delegates at the Republican convention. So entrenched were both sides that their battles allowed Democrat Woodrow Wilson to slip past them in the 1912 election, securing only 41% of the popular vote.

Sulking, perhaps because of the ego-damaging loss, or perhaps because he recognized his culpability for his party’s wreckage, Roosevelt limped off to South America for his ill-fated exploration of the River of Doubt. Taft, actually relieved by not having the burden of office upon him, wound up where he had always hoped to serve as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He could immerse himself in challenging cases without feeling the threat of political pressure.

Taft and Roosevelt did finally reunite in friendship, with Taft initiating the renewal of mutual affection. Roosevelt, enfeebled by the ravages of illness and the long-term effects of a bullet wound, had lost much of his egotistical, fiery flair. Working together, they had accomplished great things for the progressive movement, and had initiated policies that would improve the lot of the common man while checking the growth of many powerful conglomerates. But their differences in personality and courses of action had led to a devastating split, which would forever darken their personal histories.

Ted Odenwald and his wife, Shirley have lived in Oakland for 43 years. He taught HS English at Glen Rock High School for all of those years plus one more. Now he is enjoying time spent with his family, singing in the North Jersey Chorus and quenching his wanderlust. Ted is also the Worship Leader at the Ramapo Valley Baptist Church in Oakland.

Ted Odenwald and his wife, Shirley have lived in Oakland for 43 years. He taught HS English at Glen Rock High School for all of those years plus one more. Now he is enjoying time spent with his family, singing in the North Jersey Chorus and quenching his wanderlust. Ted is also the Worship Leader at the Ramapo Valley Baptist Church in Oakland.