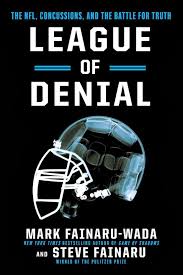

League of Denial: The NFL, Concussions, and the Battle for Truth.

By Mark Fainaru-Wada and Steve Fainaru.

New York: Crown Archetype, 2013.

As reviewed by Ted Odenwald

Former Giant great Harry Carson gave a direct, powerful and emotional speech when he was inducted into Canton, Ohio’s Pro Football Hall of Fame. He implored the NFL to do the right thing—to take care of the thousands of retired veterans and active players whose mental health has been put at risk by participation in the sport.

Former Giant great Harry Carson gave a direct, powerful and emotional speech when he was inducted into Canton, Ohio’s Pro Football Hall of Fame. He implored the NFL to do the right thing—to take care of the thousands of retired veterans and active players whose mental health has been put at risk by participation in the sport.

Carson’s eloquent plea arose from reports—based on research by neuro-psychologists and neuropathologists—that “a public health crisis [has] emerged from the playing field of our twenty-first century pastime.” The crisis has surfaced through compelling evidence that many professional football players are suffering in various stages of CTE (Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy), a progressive degenerative disease caused by concussive and non-concussive blows to the head. Many former players in their 50’s and 60’s have reported significant neurological problems: memory loss, confusion, speech or hearing problems, and headaches. Others have experienced symptoms of severe dementia, including marked personality changes, depression, and even suicidal tendencies. Autopsies of the brains of several players, who had displayed these symptoms, revealed severe internal damage caused by “taus,” the accumulations of proteins produced as a result of brain injuries; these taus surrounded nerve cells, basically strangling the brain.

Important segments of the Fainaru brothers’ study trace the history of the research into the brain damage that in part defines CTE. They follow the tragic demise of Pittsburgh Steeler Mike Webster, an all-pro center, and Junior Seau, an all-pro San Diego Charger linebacker. The details of the mental deterioration of both players are frightening. After Webster’s death, Dr. Bennet Omalu, a neuropathologist, examined sections of the athlete’s brain, discovering several areas of severe degeneration similar to that of brain-damaged boxers. The Fainarus trace the struggles of Omalu and several other researchers to get their findings out to the sports and medical worlds. Years later, there was much more interest when Seau’s suicide death led to battles between competing teams of neuropathologists, who had chosen to follow up on Omalu’s findings. Teams of doctors, competing for funding, found themselves as heavily engaged in political maneuverings as in research.

Most frustrating, disappointing, and puzzling in this search for the truth has been the NFL’s persistent state of denial—thus this book’s title and Harry Carson’s plea. In 2002, when concerns about widespread incidents of brain injury to athletes were emerging, an NFL study claimed that players “did not sustain frequent repetitive blows to the brain on a regular basis.” This astonishing denial was called into question by surveys of professional players, many of whom believed that they had suffered multiple concussions and were now experiencing cognitive difficulties. Neurologists discovered that while a first concussion might not necessarily cause permanent damage, even one subsequent concussion was likely to expose the player to severe loss of brain function. The blows to the head could “…unleash a cascading series of neurological events that in the end strangles your brain, leaving you unrecognizable.” The shallowness of the NFL’s initial concern about the occurrence of head injuries can be surmised from the title of their first study committee: “The Mild Traumatic Injury Committee.” In the past the determination of the severity of a head injury had been in the hands of the coach or the trainer. Batteries of verbal tests were developed by outsider wishing to quickly assess a player’s brain functions. Perhaps predictably, the NFL’s appointed committee sided with the NFL in key cases, claiming that football players were apparently “impervious to brain damage….”

As governmental pressures built for further investigation, the NFL turned the issue of research over to the National Institute of Health (while also giving the NIH a substantial financial gift). The NIH put together committees that excluded such researchers as Omalu (a true pioneer in the field), while accepting others whose motives appeared to be other-than-scientific. The most recent conclusion of the NIH is that “No direct cause and effect has been established.” One understandable reason for this conclusion is that the actual damage can only be observed postmortem.

Dr. Ann McKee, a neuropathologist with Boston University, stated that she “…[had] never seen this disease in the general population, only in these athletes. It’s a crisis, and anyone who doesn’t recognize the severity of the problem is in tremendous denial.” While the NFL persists in its denial of the direct connection between concussions and CTE, it has acted in a number of ways to reduce the number of incidences: strong rules including fines for hits to the head; more careful testing for the presence of concussion, and stricter requirements for determining full recoveries from concussion. The NFL arrived at a settlement of $765 million with veteran players who have claimed that football injuries have led to diminished mental capabilities. Some critics have called this settlement “chump change.” Dr. McKee might agree with this assessment as she believes that all NFL players will get this. “It’s a matter of degree.” The Fairanus believe that eventually the outcome of this concussion crisis will be resolved by a combination of attitudes –not from enemies of the game—but from the fan base, from advertisers, players, moms, dad, kids, and even some scientists.

For now, the NFL has covered itself in deniability by gaining control of scientific discussions while the public remains complicit through its love of the game.

Ted Odenwald and his wife, Shirley have lived in Oakland for 43 years. He taught HS English at Glen Rock High School for all of those years plus one more. Now he is enjoying time spent with his family, singing in the North Jersey Chorus and quenching his wanderlust. Ted is also the Worship Leader at the Ramapo Valley Baptist Church in Oakland.

Ted Odenwald and his wife, Shirley have lived in Oakland for 43 years. He taught HS English at Glen Rock High School for all of those years plus one more. Now he is enjoying time spent with his family, singing in the North Jersey Chorus and quenching his wanderlust. Ted is also the Worship Leader at the Ramapo Valley Baptist Church in Oakland.